Sunday, July 09, 2006

Navigating Continents of Origin

An editorial in The New England Journal of Medicine in 2001 said race was a "social construct, not a scientific classification," and denounced "race-based medicine," including "medical research arbitrarily based on race." The editorial concluded that "in medicine, there is only one race — the human race."

Such high-minded sentiments sound pretty good. But the same issue of the journal also included an article and another editorial suggesting there were some important racial differences in the way people reacted to various medicines, including drugs used to treat high blood pressure, heart failure, depression and pain. The differences could affect the dose a person needed, or whether a particular drug should be used at all.

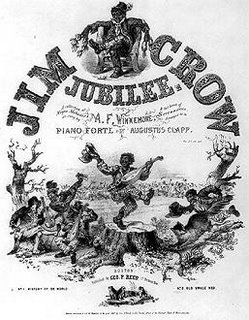

It's a very explosive issue. And for a good reason. The whole concept of race has been abused blatantly in the past and egregiously misused in order to accomplish very distasteful ends socially and politically. ...

The question remains, does any of the differential distribution of gene forms have potential medical significance? I think the answer is, sure. There may be differentially distributed genotypes that put a group, in aggregate, at increased or decreased risk for certain diseases or affect their responses to certain medications.

To avoid the charged word "race," "continent of origin" is being used more and more and may reflect the useful information better anyway. Dr. Lisa A. Carey, the medical director of the University of North Carolina at Lineberger says:

I agree with people who say race is an artificial construct. It has limited usefulness now, as a proxy for ancestral geographic region.

It's what we have. If it gives us some information it's better than no information.